[The third installment of Sheila Graham-Smith's review of my book Ullambana in Portland; the series will conclude tomorrow.]

PART 3

In the short biographical note included in the book the author calls himself, among other things, a flaneur. The word flâneur, with all its associations of wandering, observing, synthesising the city, is perfect. According to Baudelaire and Victor Fournel, the flâneur understood the city, and for Walter Benjamin his perambulations facilitated “a way through significant psychological and spiritual thresholds.” (1) Ullambana in Portland is built on the understanding gained through wandering, observing, and synthesising, but the poems in the second section especially find their various ways across those significant thresholds.

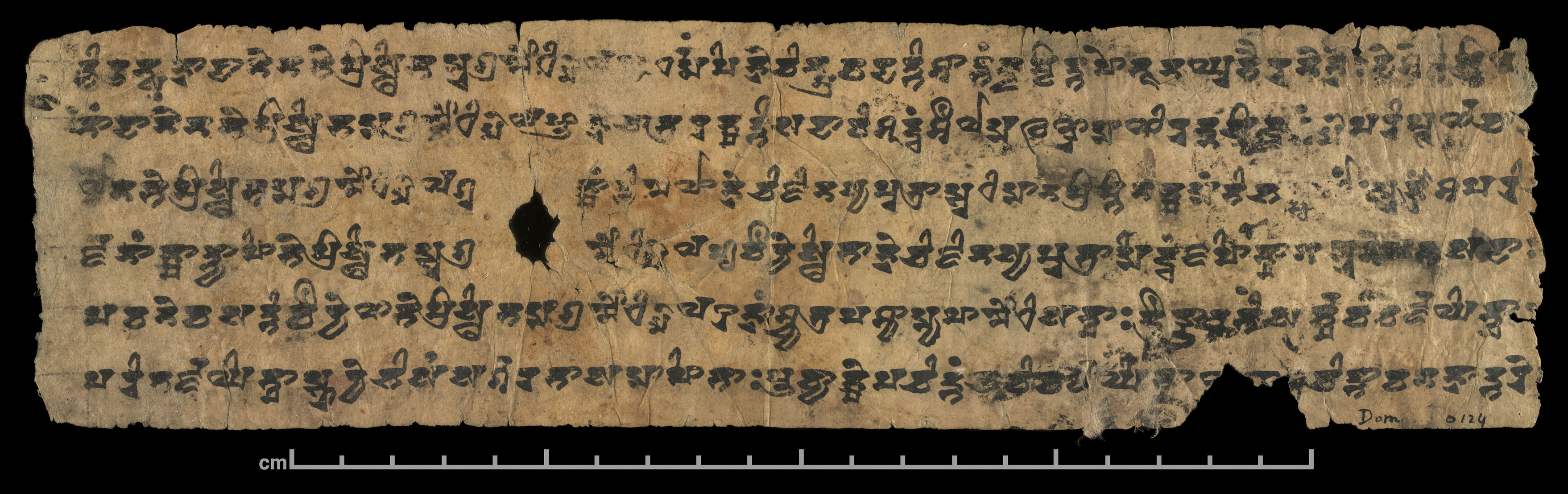

There are 16 poems called sutras in the collection, each of them dedicated to some particular person or persons, except the final one, “walking sutra”, which is the poet’s own. Sutra means, literally, string, or thread, from the root word siv, that which sews or hold things together. Wikipedia, quoting A History of Indian Literature, says “In the context of literature, sutra means a distilled collection of syllables and words, any form or manual of "aphorism, rule, direction" hanging together like threads with which the "teachings of ritual, philosophy, grammar or any field of knowledge" can be woven.” The definition is important as it points out the connecting role of the sutra poems, all of which explore, one way or another, themes related to the idea of tending, whether to people, to the world, to life, or to the ideas and thoughts that help in the struggle to make sense of any or all of this.

“cloudy day coffee sutra”, for instance, poses a series of questions that wrestle with the way language both opens and closes possibilities in the way we relate to people and the world.

what would you call that sky?

what would you call that tree?

what would you call those passersby?

what would you call that?

Why would someone ask such questions about the view from a coffee shop not far from their home? They sound as if they might be things asked by someone learning a new language, but that isn’t the case. The poet himself – plainly a more than adequate English speaker – is putting the questions to some unnamed you he is having coffee with, at the same time as he puts them to you, the reader.

what would you call that sky? dissolving to

mist unfit for paper birds all falling

ash-gray slate-gray nickel-gray falling in

counterpoint with yellow leaves—what

would you call that tree? gray limbs in taijiquan

gestures reaching & reaching—that low sky

can’t be grasped those folds upon folds of

clouds this massive origami not what it seems this

tonnage of ice & water as if the Pacific mirrored it

self in what some call heavens—

vapor rising from

two cups of coffee on this counter, trans

muted liquid: you know, language is like that

too paper birds afloat in the mind &

folded with no beginning no end the speech

of birds in an ash tree scissoring loose its

leaves, gray branches the lichen mottled cream

white milk-white what would you call those

passersby no two alike no two different all

looking for something not apparent you said

god is like that too the water droplet within the

ocean seeking the ocean -

that sky lowering, that

bird in silhouette that Chinese character’s

brushstrokes tracing black green blue in one

syllable what would you call that? quadrillion

raindrops paper birds imagined branches this

coffee steam rising up these people walking it

goes without saying all one all undiminished

A poem as intricate and complex as the origami birds it mentions, folded with no beginning or end, but one of its themes is caught in the vapour rising from two cups of coffee – “trans-/muted liquid: you know, language is like that/too”. Transmutation - the action of changing or the state of being changed into another form. “cloudy day coffee sutra” plays with this idea of change, both as it applies to the world and as it applies to the language we use to describe that world. Hayes is a self professed “dimestore Buddhist” and the poem reflects the idea that, as he puts it, “the phenomenal world is ever arising & ever renewed; just as the only actual time is ‘now’, so the only actual existence of the 10,000 phenomena is in the current instant. As such, the phenomenal world is radically dynamic, whereas the act of naming is radically static. It accounts for things in a sort of Platonic sense, but not in a dynamic sense of ‘becoming.’(2)

That ungraspable low sky, for example, a tonnage of ice and water shifting before our eyes, but captured, however imperfectly or momentarily, in “the folds upon folds of a massive origami, not what it seems, the Pacific mirroring itself in the heavens”. Not, notice, ‘as if the Pacific was mirrored in the heavens’, but ‘as if the Pacific mirrored itself in the heavens’. Lacan claimed the ‘real’ is un-representable and supersedes any attempt to give it a coherent and comprehensible form, including in language. (3) It can only be defined through paradox. According to Kierkegaard the ultimate paradox of thought is the desire to discover something that thought cannot think (4), and the “cloudy day coffee sutra” discussion of the interplay of language and reality is riddled with just that sort of thought – “the water droplet within the ocean seeking the ocean”, for instance, or “those passersby no two alike no two different”.

The tension here, is between the idea that the truth of things is inherent in their particularity, that the particularity itself is ultimate, and the idea that the truth of things is in their oneness; an issue not really resolved in the context of the poem - it couldn't possibly be – but suspended there, held up in delicate balance to be examined. Hayes has pointed out elsewhere that “as a poet one is also trying to conjure reality back into its real existence by naming it. So there is both the distancing of reality from the one, or…what is, but also the reconstruction of reality.” (5) In other words, “there are always these people walking it goes without saying all one all undiminished”.

The problem of the one and the many, reflected in the stream of images garnered from day to day life in the city, runs like another thread through much of the collection, nuancing thoughts about time and art, about memory and loss and love and desire and death, constantly challenging the reader to consider, and then to reconsider.

“new moon cello”, written after a Zoë Keating concert at the Aladdin Theatre in Portland, states its thesis in the opening line - Loss is constant across dimensions - and gives a series of beautiful examples supporting its claim –

loss is constant across the dimensions:

an entire Chinese bestiary achieving form & gone:

waning crescent moon melting to new moon’s

hollow, this improvisation soaring beyond &

beyond the vanishing point in this theater’s

sapphire light, that flock of

crows rising off a frozen pasture in March, grass

stubble ragged amidst corn snow: faces

taking form & gone—the helicopter blasting

cherry blossoms westward off

boughs in Waterfront Park that perfect

blue Thursday, sun a halo of

grief: now May, & ghostly

rhododendrons nod—notes swell

& fade & swell & fade, the sinews drawing

pangs travail transcendence across

four strings to that foursquare city built beyond time

“It’s in the nature of things”, as Ms Keating said after she played a beautiful improvisation to open the concert, only to discover the sound man hadn’t recorded it. Another loss, and if you know Zoe Keating’s work, you know it was a significant loss, however true her response may have been. Meanwhile, outside the theatre, in the wider city:

black Willamette

rolling past bridge lights, polyphony rolling past

stage lights now violet now emerald opal amber;

the heart’s daily shattering

There is a clear parallel between the way Keating’s music and Hayes’ poetry is constructed. Lou Fancher, in her article "In the Loop with Zoë Keating" uses the word ‘polydimensionality’ to describe the effect created through the layering of music saved and looped through a computer and the music being produced in any given instant of a performance, (6) and it applies perfectly to the way Hayes’ simultaneously produces and builds on a relentless flow of imagery. In a 2010 interview, he mentions that “if you have these very fluid & rarely ever end-stopped lines & you rely a great deal on sensory data (as opposed to abstract concept or pure language) to construct a poem, that sensory data may seem overwhelming”; but he also connects it explicitly to “the idea of poetic writing as improvisation” and the need “to start at a point & develop the idea in different directions”. (7)

There is meaning embedded in each image, in the juxtaposition of images, the layering of images, in the memories evoked by the images and the thoughts provoked by them, in the echoes, the trajectories of joy and the half life of pain, in the restless ghosts and the quiet ones. Analysis fails to do justice to either Hayes poetry or Keating music. Its significance is as much in the flow and shift as in the unified whole that emerges in the end.

“new moon cello” moves to a close with an allusion to another moment of personal loss, and then, significantly to the mention of two women bent over great pieces of art;

you absorbed in a poem where a butterfly disappears

within crimson blossoms: dark cello,

waxing crescent silver hair wave, eyes closed in unlit

night amongst such profusion of quavers our incarnations

brief & brief then brief again

Significantly, the lines of the Du Fu poem that absorb the poem’s you are left in the darkness at the margins of Hayes’ poem and Zoë Keating’s performance, but they comment beautifully on both the poetry’s and the music’s profusion of quavers and on their incarnations brief & brief then brief again.

the wind & light proclaim flow & shift as one:

why should we not enjoy time’s brief passage?

crooked river #2, Du Fu 曲江二首 (translation by Jack Hayes)

Sheila Graham-Smith

© 2016

1. Bobby Seal, “Baudelaire, Benjamin and the Birth of the Flâneur”, Psychogeographic Review - http://psychogeographicreview.com/baudelaire-benjamin-and-the-birth-of-the-flaneur/

2. Jack Hayes, private correspondence

3. Stephen Ross, “A Very Brief Introduction to Lacan”, University of Victoria. http://web.uvic.ca/~saross/lacan.html

4. Soren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Fragments Chapter 3 The Absolute Paradox - A Metaphysical Caprice

5. Jack Hayes, private correspondence

6. Lou Fancher, "In the Loop with Zoë Keating" - https://www.sfcv.org/events-calendar/artist-spotlight/in-the-loop-with-zoe-keating

7. Sheila Graham-Smith, “An Interview with John Hayes, Author of The Spring Ghazals”, Tangerine Tree Press and the Tangerine Tree Press Review. November 12, 2010. http://tangerinetreepress.blogspot.com/2010/11/interview-with-john-hayes-author-of.html

Please check back tomorrow for part 4 of Sheila Graham-Smith's review.

Information on the Images:

1. Steel Bridge & Chinese junk: photo © John Hayes

2. A Sanskrit manuscript page of Lotus Sutra (Buddhism) from South Turkestan in Brahmi script. Public domain. Image links to its source on Wiki Commons.

3. Aladdin Theater Sign: photo © John Hayes

4. Cherry blossoms at Waterfront Park: photo © John Hayes

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for stopping by & sharing your thoughts. Please do note, however, that this blog no longer accepts anonymous comments. All comments are moderated. Thanks for your patience.