at autumn’s end, frost and

dew hanging heavy,

rise at dawn to walk

through a hidden valley—

yellow leaves have

enveloped the creek bridge,

in the deserted village,

nothing but ancient trees—

winter blossoms here and

there, sparse and lonely,

the stream’s murmur cut

off, then picks up again—

my heart’s desires long

since have been put aside:

what is it that startles

the milu deer?

Based on Liu Zongyuan: 秋曉行南谷經荒村

Qiū Xiăo Xíng Nán Gŭ Jīng

Huāng Cūn

Note: Milu—also known as Père David’s deer—are essentially

extinct in the wild, though a small feral population does currently exist in

China, composed of a herd that escaped a zoo. Otherwise, the milu only exist in

zoos. Dating back to prehistorical times, milu ranged across all of China,

though the population shrank steadily during historical times. The milu are

sometimes called “sibuxiang” (Chinese: 四不像; pinyin: sì bú xiàng), which could

be translated as “four not alike”; they are variously described as having

"the hooves of a cow but not a cow, the neck of a camel but not a camel,

antlers of a deer but not a deer, the tail of a donkey but not a donkey";

"the nose of a cow but not a cow, the antlers of a deer but not a deer,

the body of a donkey but not a donkey, tail of a horse but not a horse";

"the tail of a donkey, the head of a horse, the hoofs of a cow, the

antlers of a deer"; "the neck of a camel, the hoofs of a cow, the

tail of a donkey, the antlers of a deer"; "the antlers of a deer, the

head of a horse and the body of a cow".

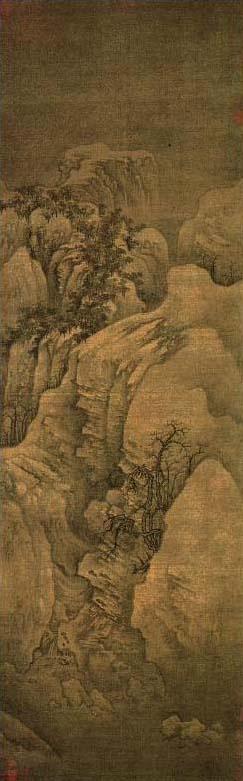

Image links to its

source on Wiki Commons:

“Snow Mountains”: Guo

Xi. 11th Century. Public domain.

_MET_TR_171_1_2013_O1_sf.jpg)