Chang’e

on the candlelit mica

screen, a distant shadow;

Heaven's River ebbs

slowly, the morning star sinks low—

Chang’e must regret

stealing the elixir of life:

blue of sea, blue of sky,

her dark heart, night after night

translation © Jack Hayes 2017

based on Li Shangyin: 嫦娥

Cháng'é

Mid-Autumn Moon

insects hidden under

grass, frost atop the leaves;

a vermilion balcony

presses against the bright lake—

the Rabbit chilled, the

Toad cold, the Cassia blossoms white:

this night must be

gut-wrenching for Chang’e

based on Li Shangyin: 月夕

yuè xī

Frost Moon

once expeditionary geese

are heard, cicadas fall silent;

the hundred-foot tower

connects river and sky—

Blue Maiden and White Lady

both can endure cold;

in the moon, within frost,

they compete in beauty

based on Li Shangyin: 霜月

shuāng yuè

Notes:

This set of translations

would be more appropriate for the Mid Autumn Festival, Zhōngqiū Jié, which is

the full moon closest to the Autumn Equinox. But rather wait until next

September, I’m posting them now.

We have no way of knowing

whether Li Shangyin intended these poems as a complementary set or as distinct

& individual compositions. James JY Liu in his seminal work on the poet,

The Poetry of Li Shang-yin: Ninth-Century Baroque Chinese Poet, does place the

poems together & discuss them as a group. Poet David Young also places the

poems together under the title “Three for the Goddess of the Moon” in his Five T'ang Poets. Since Young

is a poet & not a Sinologist, I assume in grouping the poems together he is

following Liu either directly or at second or third hand.

For more information on

the Chang’e myth, see the Wikipedia page. Briefly, Chang’e stole the elixir of

immortality & flew to the moon, where she lives with a rabbit (or hare) who

pounds herbs into the elixir of immortality with a mortar & pestle & a

three-legged toad. There is also a cassia tree on the moon in this myth.

Chang’e is the “White Lady” mentioned in the third poem (素娥, sù é), while the

Blue Maiden (青女, qīng nŭ) is Qing Nu, the Goddess of Frost & Winter.

As is the case with almost

all the Chinese translations, grateful acknowledgment is due to Sheila

Graham-Smith, who did a marvelous job of elucidating the first line of the

first poem.

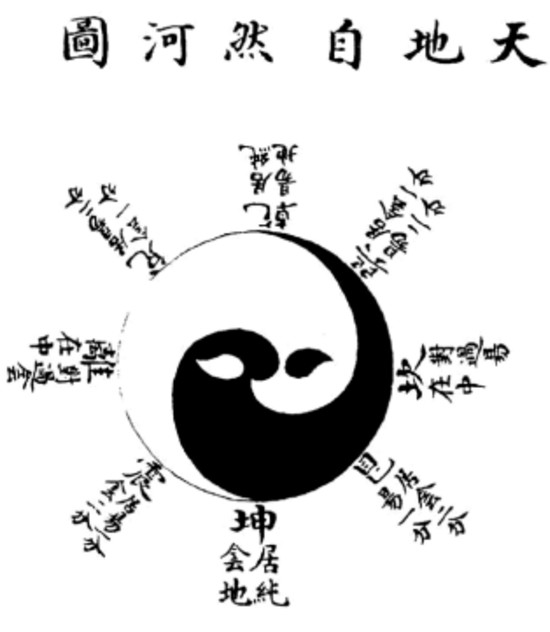

Image links to it

source on Wiki Commons:

Chang'e flees to the

moon: from Yoshitoshi’s 100 Aspects of the Moon. (1885-1892)

Public domain.

.jpg)